For Vibraphone, Marimba, String quartet, Piano & Accordion.

Four-note chords inspired by English mathematician Leonard Soicher, from Queen Mary's University. 15 minutes, 18€.

For multiple percussionists; see the percussion section.

For percussions; includes duets and trios. See percussion section.

For nine different plucked string instruments. Dedicated to Jean-Paul Davalan, the mathematician who computed many of these tilings. One movement, 26 minutes; 29€.

An excellent 2017 recording is available, courtesy of the Partch/Just Strings ensemble and MicroFest Records.

Some 20 movements count to seven in some 20 languages. See detailed description.

Flexible instrumentation. One movement, 6 minutes; 10 pages, 13€.

Flexible instrumentation. The 48 all-interval tetrachords, arranged for two monodic instruments. 23 pages, 15€.

For two flutes, oboe, clarinet, two violins and viola. All composed with mathematical techniques, but each quite different. Average duration 10 minutes. Full score can be downloaded here for free; parts are available for 20€ per piece.

For there is nothing hidden, but it must be disclosed, nothing kept secret except to be brought to light. Anyone who has ears for listening should listen.

Marc 4.22-24

These septets evolved over a long period, beginning with “11 Chords” (originally called simply Septet), written and premiered in a festival in Holland in 2007, then “16 Gammes” the following year. “Valse” was written in 2010, but never performed, and I didn’t make much effort to find a performance for it, because I was sure that this combination of two flutes, oboe, clarinet, two violins, and viola could lead to a substantial series of music that would be rather special. The differences in color, all within the same range, made possible textures very different from the normal instrumental combinations intended for SATB voicings. My music is generally more concerned with notes than with timbres, and often the instrumentation is not specified at all, but this was different.

“Pavage” came a few years later, and then in 2014, when it became clear that the ensemble Offrandes in Le Mans was willing to learn and perform a whole series of such pieces, I went to work full time until I had enough pieces to make a whole concert. “Trichords & tetrachords” is dedicated to my mathematician friend Franck Jedrzejewski, who researched homometric pairs, which was the key idea for structuring that music. “Courir-Attendre” (run-wait) came out of a logical family of 90 different seven-note chords distributed into six running sections and six waiting sections of 15 chords each. “Catalogue” contained all the seven-note chords possible in one octave, which was exactly the content of one section of the Chord Catalogue (1985), though ordered completely differently. The final work all took place in 2015, when Ensemble Offrandes began rehearsing the music for premiers in 2016 in Le Mans, Alençon and other locations in the Loire valley and elsewhere. I am particularly grateful to Samuel Boré, who organized this project for Offrandes, to Fabrice Villard, who played the clarinet and served as musical director, and to all the fine musicians from Le Mans and Alençon who became quite engaged in the project and played very well.

In the quotation at the beginning of this text, taken from the gospel of Marc, Christ was talking about how to listen to parables, but I think it is good advice for listeners of this music too. One doesn’t need to be either a mathematician or a musician to perceive that two chords may be the same or different, or almost the same or almost different, or to hear that two instruments are playing the same melody in the same tempo, or that the music is structured in simple symmetrical forms. What the listener gets out of the music is proportional to the curiosity and concentration he or she puts into it.

This music is essentially a long progression of five-note chords, and the sound must be homogenous enough to be able to hear the harmonies clearly, yet subtle color differences greatly improve the musical interest, so it seemed best to solve this problem myself. I intentionally broke all the usual laws of voice leading, and crossed voices very often, so that one would hear the chords independently, without melodic connections.

The chords are constructed on an 11-note scale in a rather narrow range, following a combinatorial design known as (11,5,2), which means that:

I simply took the unique solution for this rather amazing symmetrical structure, transformed it into 10 related solutions, as shown on the cover, selected my 11-note scale, and arranged the result for the selected instruments. The total duration is about 12 minutes.

Samuel Vriezen is the first composer to make music with this combinatorial design, and it was his example that stimulated my music.

Those wishing to know more about the mathematics of these sorts of structures may consult The Handbook of Combinatorial Designs, edited by Charles J. Colbourn and Jeffrey H. Dinitz (second edition, Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2007)

Full score available here: Septet I: 11 Chords.

This septet comes from a classic combinatorial design found at the beginning of almost every text on the subject, and it can be clearly seen in geometrical form.

Seven points are covered by six lines and by one little circle that is considered to be a seventh line. Each point intersects with three lines, each pair of points comes together on one line, each line shares one point with each other line, and this information can be summarized by saying simply that it is a (7,3,1) design. It seemed obvious that seven three-note chords following this structure would make lovely symmetrical music, but for several years I couldn’t find the best seven notes for these seven chords. I finally realized that the mathematics is strong enough that convincing music results with almost any set of seven notes. Thus each of the 128 measures of this piece is another realization of the classic seven-line diagram, following 16 seven-note scales in eight different ways, and all 128 solutions sound fine to me. The results were often surprising, however, because each new set of seven chords, each new scale, turned out to be something I had never heard before. It was hard to believe that this was really my music, as it seemed to be coming from somewhere else, perhaps from that idealistic zone that Plato defined as pure numbers.

Full score available here: Septet II: 16 Scales.

This piece is a mechanical sounding little waltz that takes a long time to go nowhere in particular, but you will probably find that it does not sound trivial, and in fact, you will need time to enter into this little machine and begin to hear how it is working.

The music follows the block design (10,4,2) but this is a “large (10,4,2)”, which means that it uses not a single 15-chord solution, but 14 different ones, calculated so that by the end of the piece we have heard once chord each, all 210 of the possible four-note combinations one can form with a scale of 10 notes. In each section the 15 chords are heard three times each, each pair of notes comes together once, each measure contains two notes that are common to the preceding measure and two that are common to the following measure, and additional symmetries are so numerous that trying to find all of them would be an endless task.

Franck Jedrzejewski calculated the 14 (10,4,2) designs for me, following procedures defined by Kramer, Magliveras and Stinson in the Australasian Journal of Combinatorics (1991).

Full score available here: Septet III: Valse.

In the monthly meetings of MaMuX, organized by Moreno Andreatta at IRCAM in 2001-2010, many theoreticians and mathematicians came together to discuss subjects pertaining to music and mathematics, and I was almost always present.

One of our main subjects was tiling the line or rhythmic canons, that is, how do you write a rhythm that can be played in canon in several voices in such a manner that no two instruments play at once and no point in time is left empty?

The mathematician Emmanuel Amiot made particularly astute observations in this area, and this piece is dedicated to him.

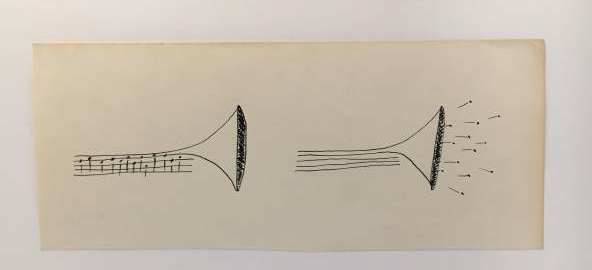

A perfect tiling is one in which a line may be tiled by combining a simple rhythm in several different tempos. The shortest perfect tiling of a simple tatata rhythm is in five voices, with tempos 7 : 5 : 4 : 2 : 1, as shown here;

each point is covered, without overlaps. This became Tilework for Piano, in 2003.

In November of that year I delivered a lecture at IRCAM in Paris on Perfect Triplet Tilings in One Dimension, where I was able to go a little further. Working with the Austrian mathematician Erich Neuwirth, we determined that no solution exists for tiling a line of 18 points in six voices, but that one may tile a 21-point line with seven voices in nine different ways.

Seven years later, in 2010, as I was working on my septets, it occurred to me that I should now be able to find a musical application for our seven-voice perfect tilings. After trying several other approaches, I realized that the seven-voice counterpoint would be heard most clearly using a three-note scale, with the instruments all playing the same three notes in their individual tempos, the scale expanding with each solution.

In each section we hear the complete tiling twice, with all seven voices, then with only six voices, then 5 voices, 4, 3, 2, and 1, making the individual voices more audible. One of the nine solutions, the last one, where the voices play in proportions 10 : 8 : 7 : 5 : 4 : 2 : 1, is shown here.

Full score available here: Septet IV: Pavage.

If one forms scales of seven notes, the intervals between adjacent notes being two minor seconds, two major seconds, and two minor thirds, the intervals may be ordered in 90 different ways, producing 90 different scales. The fast music here, the “courir” sections, simply run from one of these scales to another, while the slow music, the “attendre” sections, follow the same seven-note modes in the form of a very slow chorale, and that pretty much explains everything.

The piece was mostly written in 2010, but I kept going back to it and changing things, and didn’t finish a definitive score until 2015.

Full score available here: Septet V: Courir-Attendre.

This composition is dedicated to Franck Jedrzejwski, as it was he who got me interested in one of his favorite subjects, homometric pairs of chords, that is, two chords that may look very different, though the collection of intervals between the notes is the same. Allen Forte, writing about serial music in The Structure of Atonal Music (1973), already noted the existence of such pairs, but hardly any composers have explored this in a way that allows us to hear the phenomenon. The 48 chords resulting from the transpositions and inversions of this particular homometric pair of seven-note chords from Forte’s list divided nicely into configurations of thee notes for the three string players and four notes for the winds. I rotated the 48 chords in such a way that the notes are quite different with each new chord, and the chords never repeat, and yet the music as a whole sounds quite uniform.

Full score available here: Septet VI: Trichords & Tetrachords.

I had already put together the 1716 seven-note chords possible in one octave as part of my Chord Catalogue (1985), and it seemed natural to just compose another catalogue of seven note chords for my seven melodic instruments, but of course, the Chord Catalogue was normally played as a piano solo, and you can’t just transcribe keyboard music for an ensemble of instruments, so a septet version required a whole new way of thinking. I had just written the theoretical book Other Harmony, where I talk about how chords can be grouped when the sum of their notes leaves the same remainder when divided by the number of notes. So in this case the chords can be separated into seven subsets, depending on whether the sum of their notes, divided by seven, leaves a remainder of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6.

Within one of these subsets, the only way to move from one chord to another without changing more than one voice is for that voice to move up or down a perfect fifth. That makes little difference in the sound of the chord, so I could move through each subset with almost inaudible differences. Some of the chords came in very large, complicated families, so I decided to eliminate many of the 1716 chords and just use those that fell together neatly in sets of 8, 4, 2, and 1. The resulting score contains 926 chords instead of all 1716, but that is already quite long enough for the musicians – and for the listeners. The “Catalogue” septet ended up requiring more research and more composing time than any of the other septets, because calculating all those chords precisely, not leaving any out, and making sure that some chord with a remainder of two didn’t get mixed up with the chords having remainders of three required much correcting, and finally, I suspect that there are still a few errors, but not ones that you will hear.

Full score available here: Septet VII: Catalogue.

A rather long score for six jugglers throwing at least 20 different sounding balls, maracas or shakers, with lots of stage directions. 15€.

Seven kinds of music derived from seven drawings all based on a (12,3,2) combinatorial design. About 20 minutes. The three B-flat clarinets each read from the score. 21€.

Written for Gandini Juggling, this marks the first time a composer has written for jugglers, and perhaps the first time three jugglers have performed with amazing musical precission. The premier in Amsterdam was with sounding balls developed by Steim researchers. 13€.

The falling thirds are played by some solo instrument, the drum keeps the beat, and everything is the result of a drawing. Eight minutes, 13€.

Three percussionists [one cowbell, one wood block, one bongo] seem to be “mocking” one another as they progress from one rhythm to another slightly different rhythm, all nicely charted in graphic illustrations. By the end of seven minutes, each of the rhythms has been played once and none has been repeated. Dur. about 7 min. Score 15€.

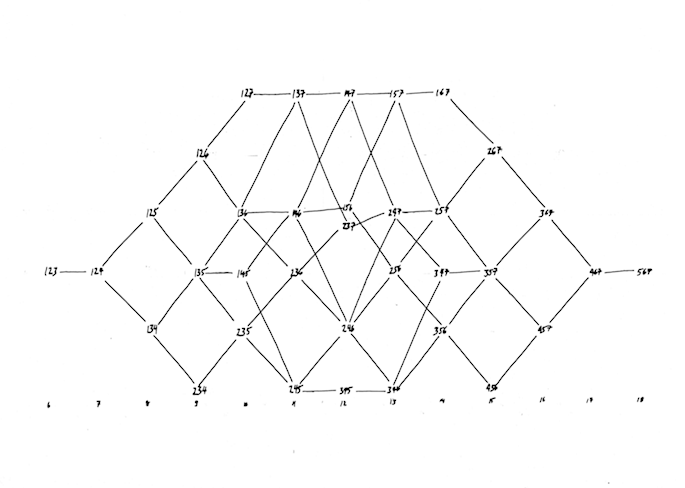

For some time I have enjoyed calculating graphs in order to see how one could progress through a whole group of chords, always following the most subtle voice leading possible. Only one voice is permitted to move one degree up or down. In the case of Mocking I did the same thing with rhythms. To have two notes in the time of eight beats, for example, the possibilities are to play on beats 1-2, 1-3, 1-4, 1-5… up to 7-8. There are a total of 28 different two-note rhythms, and the ways in which these can be joined with minimal differences can be seen in the graph on the first page. The subsequent sections of the music follow the same procedure with rhythms of three, four, five and six notes. So by the end we have a little catalogue of all 256 rhythms possible in 8 beats, omitting the eight rhythms of one note and the eight rhythms of seven notes, which both musically and mathematically are almost as trivial as the remaining rhythm with zero notes.

The clearest way of organizing this little catalogue was to follow the graphs from left to right, playing each rhythm once, and the clearest way of hearing them was just to pass them from one simple percussion instrument to another. As I began scoring the sequences for cow bell, wood block and bongo, and listening to the results in my head, the three percussionists seemed to be competing with one another, correcting one another, making fun of one another, or in a word, Mocking one another. Thus the title.

Tom Johnson, Paris 2009

Vermont Rhythms is written for 2 saxophones (tenor and baritone), trombone, percussion, guitar and keyboard. Two Vermont mathematicians constructed a remarkably symmetrical list that includes all the 462 six-note rhythms playable in a measure of 11 beats. This permitted the composer to write 462 measure of syncopations that are as different from jazz as from Stravinsky. Written for the professional Dutch sextet Ensemble Klang, the score is not recommended for part-time ensembles. Score 25€, parts 23€.

CD recording available by Ensemble Klang.

This piece is called Vermont Rhythms because it would never have been written without the cooperation of two Vermont mathematicians, working at the University of Vermont in Burlington. In answer to a question of mine, Susan Janiszewski, with her advisor, Professor Jeffrey H. Dinitz, constructed a remarkable list of all the 462 six-note rhythms possible in an 11-beat period. Their impressive list distributes the rhythms in 42 groups of 11, each group forming an 11 by 11 square. The first square, the first 11 measures of music, is shown on the cover, so that one can better appreciate the symmetry of these squares. All 42 squares contain six elements in each row and six elements in each column, giving maximal rhythmic variety within the 11 phrases of each square. Each six-note rhythm has exactly three beats in common with each of the 10 others, and mathematicians will appreciate additional symmetries in these configurations.

My primary interest was the 462 rhythms, but I soon realized that I could choose pitches by employing the 462 six-note chords possible on an 11-note scale at the same time, so I did that too. Of course, much of this organization will not be heard consciously, even by very astute listeners, but some of it will be quite clear to everyone, and it is satisfying to know that many unheard symmetries are also present, reflecting one another in the background.

As the piece became clearer in my mind, I realized it would be particularly effective played by Klang, an ensemble in The Hague that had recently done an amazing interpretation of Narayana’s Cows. They agreed to premier the work, which explains why it is scored for two saxophones, trombone, guitar, percussion, and piano. The music has little to do with instrumental color, however, so the instrumentation may be varied somewhat to be more suitable for other ensembles.

Tom Johnson, Paris, December 2008

Harmonies derived from block designs for flexible instrumentation with lots of explanation. Play as long as you want. 18€.

A trio with flexible instrumentation (violin, viola and cello for example), originallly written for accordeonist Maik Hester in 2005. All the numbers 1 to 19 in subsets of three that have sums of 30 or 31. 10€.

Rational harmonies in five voices for amplified ensemble (solo 1, solo 2, keyboard, guitar and bass). 20 minutes. Score 18€, parts 23€.

CD recording available by Ensemble Klang.

After some months of work and hundreds of experiments, the music that finally became 844 Chords was defined with a few remarkably simple rules: Use only the intervals between the minor third and the octave. Begin with the five-note chord where the intervals between the instruments are 3, 4, 5, and 6 semitones, which give a total of 18 semitones, an octave and a half. Continue with the four chords having a total of 19 semitones: (4,4,5,6), (3,5,5,6), (3,4,6,6), and (3,4,5,7) and ask the computer to continue this logic with the 9 chords having a total of 20, the 16 having a total of 21, and so on. The result was a tonal-atonal mathematical sequence with inevitable regularity, but at the same time, with continually surprising juxtapositions and modulations. Sometimes one even hears reappearances of chromatic harmonies from the era of Franck and Wagner, though their sensuality is essentially arithmetic rather than emotional. The 136 chords having a sum of 31 bring us to a cadence in G major that seems to have been prepared for a long time, and I found it unthinkable to continue the logic beyond this point, chord 844.

At first the piece seemed destined to be for a classical string quintet, but the energy of the harmonic progressions required a driving rhythm and a louder sound, so I scored it for two solo lines, guitar, bass and synthesizer. The piece lasts about 20 minutes.

Rational harmonies in three voices, preferably for three flutes, or solo harp. Score: 16€.

Available on a CD recording by Manuel Zurria.

In 1847 Reverend Thomas Penyngton Kirkman, an English pastor who was also an amateur mathematician, proposed several solutions to this problem:

Fifteen young ladies in a school walk out three abreast for seven days in succession; it is required to arrange them daily so that no two shall walk twice abreast. (Ladies and Gentleman's Diary, Query VI, p.48)

His work can be considered the first “block design,” a subject that was to become a serious study in combinatorial mathematics. Of course, the discussion quickly grew to include all sorts of investigations of the possible combinations of sub-groups within larger groups, and even the original 15-ladies problem did not end with Kirkman, as mathematicians began to wonder whether it would be possible for the ladies to continue their daily walks for a complete semester of 13 weeks, so as to include all 455 possible three-lady combinations, once each. It was not until 1974 that R. H. F. Denniston of the University of Leicester published a solution, probably the only one, and thanks to him, I can now give you the music. Each lady/note appears once in the daily phrases of five chords, each pair of ladies walks together once a week, and by the end of the 13 weeks, about 13 minutes in musical time, all 455 possible trios of women have passed by, as have the 455 chords that represent them. I am particularly indebted to Paul Denny, a computer scientist at the University of Auckland, whose correspondence helped me to find this information and to understand it.

I like to imagine my three-note chords played by three flutes, or as a harp solo, though an interpretation with three oboes, three strings or one vibraphone might also be just fine, and since the music is really only notes and numbers, I would not want to prevent one from playing it on the piano or with some other instruments. We should leave the chords in this register though, and always keep the ladies clean and pretty. It seems safe to assume that the sun is always shining - otherwise they would not be taking walks.

288 three-note chords with sums of 72 (middle C = 24), preferably for violin, viola, violoncello. Score and parts 10€.

As in all the music in the Rational Harmonies series, I want to deduce my chords, rather than choosing them according to the usual musical and esthetic criteria. To compose the Trio I defined a chromatic scale with notes numbered 0 to 48 and counted all the combinations of three notes having sums of 72, permitting octave relationships, but not unisons. Then I found a chain connecting all 288 chords, requiring that each chord have one note in common with each subsequent chord, the remaining two voices moving by half steps in contrary motion with no crossing of voices. The performers may wish to make little glissandos as they move from one chord to the next.

The piece seems best as a trio for violin, viola and cello, with a tempo of about mm. 40 and a duration of about seven minutes, although interpreters may transpose and arrange the music in other ways if they wish. Faster tempos may be tried as well, although it is important that we hear harmonies and not melodic motion.

The music is constructed by systematically taking all the combinations of something, but each movement does this in a quite different way. Commisioned by MärzMusik in Berlin, for the premier by the Bozzini Quartet in MärzMusik 2004. 25 minutes. Score 21€, parts 25€.

The piece contains five movements, and each of these contains all the combinations of something. As usual, I wanted the music to know what it was doing, to be correct and complete in a rigorous sense, and this is one way of achieving this. The theory of combinations is a totally explored mathematical discipline, as we have known for more than a century how to calculate all kinds of combinations and probabilities, and how to prove all of this. So what I say about my composition can not have fundamental significance for mathematics. I can, however, demonstrate that new questions arrive when one wants to go inside some set of combinations, to see how they come together, to observe the many symmetries within them, to find the best sequence for them, to consider how they might sound, to turn them into music.

Tilework for String Quartet is a compilation of all the ways one can tile a line of 12 points by overlapping a single six-note rhythm. The four musicians play these rhythms in canon for 10 minutes in a rapid music requiring great precision. The work was premiered in a KlangAktion concert in Münich in December, 2004. Score 13€, parts 13€.

“Tilework” has to do with fitting together little tiles to fill lines and loops. One can think of this as making mosaics in one dimension, but it is also very much like stringing beads onto necklaces in various patterns. In musical terms, the Tilework series is a collection of compositions in which individual tiles/rhythms fit together into musical sequences without simultaneities, often filling all the available points of a line or a loop.

Since the notes of different motifs come at different moments, it is possible for a single melodic instrument to play several voices at once, so “tiling” was particularly appropriate for unaccompanied melodic instruments. I gradually found so many ways of tiling musical phrases that I could not stop until I had a piece for each instrument of the orchestra. The year of 2002 was devoted almost exclusively to 14 pieces for 14 solo wind and string instruments. Tilework for Five Conductors and One Drummer, Tilework for Piano, and Tilework for String Quartet came later, in 2003.

At first, interlocking one tile with another seemed obvious, sort of like fitting together the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. As the work went on, however, it became clear that this was not so simple. Sometimes it is not at all obvious how rhythms/tiles link together, and sometimes one can easily see six ways of solving a certain problem, without being sure if some seventh solution might also be possible, and sometimes the discussion can go way beyond the comprehension of musicians. I knew that making a loop of 16 beats by repeating one eight-note rhythm had something to do with group theory, and I was dimly aware that some mathematicians know how to determine the number of unique necklaces of length n possible using beads of m colors, never allowing two beads of the same color to touch, but I certainly hadn’t studied such things. Gradually I was entering a world I didn’t know much about.

As the Tilework project continued, I sometimes stumbled across questions that were as new and interesting for mathematicians as for myself. I owe much to the regular meetings devoted to Mathematical Music Theory at IRCAM in Paris, where I met many mathematicians, particularly Emmanuel Amiot, and Andranik Tangian, who gave me solutions to some problems. In the case of Tilework for String Quartet, which involves ways of tiling the line with six-note rhythms, I am particularly indebted to Harald Fripertinger and his most useful computer list of “rhythmic canons.”

But of course, composers, interpreters, and listeners do not need to know all this, just as we do not need to master counterpoint in order to appreciate a Bach fugue. As always, one of the wonderful things about music is that it allows us to perceive directly things that we would never understand intellectually.

Tom Johnson, Paris, October 2003

Variations on a 20-beat loop that turns continually around the eight instruments: flute, clarinet, trumpet, trombone, marimba, violin, viola, cello. Dur. 16 min, score 21€, parts 34€.

Four logical progressions for four instruments, each playing independently from the others. Clarinet, trombone, piano, and cello. 10-12 minutes, 13€.

The first Johnson string quartet, premiered by the Brindisi Quartet in 1994. Eight movements, each following a mathematical formula. 20 minutes, score 13€, parts 20€.

See title. Six minutes; full score 17€, parts 22€.

Trio for saxophone, guitar and bass, written for the German ensemble Ugly Culture. The title means “Unison Polyrhythms.” 18 minutes, 17€ (performers play from the full score).

For three instruments (flexible instrumentation) ; see detailed description.

For three voices (flexible instrumentation, preferably large ensembles) ; see detailed description.

Predictable music for violin, cello and piano, 15 minutes. Score, including string parts: 26€.

I studied composition with several different teachers, and in general they disagreed about everything. One thing they all agreed about, however, was that music must never be too predictable. If listeners know what will happen next, they will completely lose interest in the music. This may seem obvious, but I gradually realized that, at least as far as my own music is concerned, it is completely wrong. As I began, around 1978, to concentrate on rigorous logical sequences, I often found that the most fascinating sections, the ones that held my attention the most, were precisely the ones that were the most predictable. Thus when the Clementi Trio asked me to write a piano trio, to be premiered at the Ferienkurs für Neue Musik in Darmstadt in 1984, I decided to write a suite of short movement that would be called "Predictables."

The result really is quite predictable for anyone who is listening attentively, and it sounds a little like Beethoven as well. Writing a piano trio that won't sound like Beethoven must be at least as difficult as writing a piece for flute harp and cello that won't sound like Ravel, and I don't see any reason to deny the traditional character of this particular combination of instruments.

The subtle differences between the colors of these two instruments continue for 16 minutes. Harp and piano: 15€.

Four movements for wind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn). 20 minutes. Musicians read from the score, 15€.

A suite of short pieces for unspecified upper-register instruments. 20 minutes. Score 13€, parts 24€.

Nine short movements in eight minutes, always with the same sequence of 60 notes. 12€.

Baritone sax, guitar, and bass make their way through 20 different musical fragments, following signals called out by the leader. Usually about 10 minutes, 7€.